There's a conversation happening in every security operations center that nobody wants to have. It usually starts during budget planning, surfaces again after a breach investigation, and repeats whenever someone suggests adding a new log source.

"How much will that cost us per month?"

The question itself reveals the problem. Security teams have been conditioned to think about visibility as an expense to be minimized rather than a capability to be maximized. And it's not paranoia. The math really is that brutal.

Traditional SIEM pricing has created an environment where the foundational principle of security monitoring (collect everything, analyze everything) is economically impossible for most organizations. You're not just paying to ingest data. You're paying to store it, index it, and query it. And when those bills arrive, you're forced into decisions that create the exact blind spots attackers exploit.

Every security architect knows this calculation by heart. You've got three variables, and you can only optimize for two:

Data volume. How much are you collecting? Every endpoint, every authentication event, every cloud API call, every application log generates telemetry. Modern enterprises produce terabytes of security data daily.

Retention period. How far back can you look? Compliance frameworks demand years. Forensic investigations often need months. But every day you keep data costs money.

Budget. The actual dollars available, which are never enough.

Pick two. If you want comprehensive data collection and long retention, your budget explodes. If you want affordable operations and complete visibility, you're deleting data after 30 days. If you want to stay within budget and meet retention requirements, you're getting selective about what you collect.

This isn't hypothetical. I've watched security teams make these choices:

Skip verbose application logs because they're too noisy. Ignore DNS query logs because the volume is overwhelming. Set aggressive sampling rates on cloud resource logs. Archive anything older than 90 days to cold storage that takes hours to access, if you can access it at all.

Each decision is rational. Each decision creates a gap.

The dangerous part isn't what you're collecting. It's what you're not.

NetFlow data shows network communication patterns. But at scale, it's massive, easily the largest single source of data in most environments. Organizations either don't collect it, sample it aggressively, or dump it after two weeks.

DNS logs tell you what systems are talking to what domains. Gold for detecting command-and-control traffic, data exfiltration, and malware callbacks. Also incredibly verbose. Most organizations either skip them or filter them so heavily they miss the subtle patterns that matter.

Proxy and firewall logs. Application-layer telemetry. Verbose authentication events showing failed attempts, not just successes. Cloud resource access patterns that only reveal anomalies when you look at months of baseline behavior.

These aren't "nice to have" data sources. They're often the only place certain attacks leave traces. Advanced persistent threats don't announce themselves with high-confidence alerts. They blend in. They move slowly. They use legitimate credentials and authorized tools. The only way to spot them is by correlating low-fidelity signals across long time windows.

But if you're not collecting those signals because they cost too much? You're not finding those threats.

The invoice from your SIEM vendor is visible. The cost of not having data is invisible until it's too late.

When you're investigating a breach and realize the attacker was in your environment for six months, but you only kept three months of logs, that's a cost. When you can't prove compliance because you don't have the audit trail regulators want to see, that's a cost. When your threat hunting team spends hours manually stitching together partial pictures from multiple systems because you don't have comprehensive telemetry in one place, that's a cost.

The incident response firm that has to tell you, "We can't determine initial access because those logs don't exist anymore"? That's a cost you feel in your gut.

And here's what keeps security leaders up at night: you can't calculate the cost until after you need the data. You make the retention decision in January. The breach happened in March. You discover it in September. The logs that would tell you how they got in were deleted in June.

Legacy SIEM economics are built on coupling. Storage is coupled to compute. Indexing is coupled to ingestion. The cost of collecting data is inseparable from the cost of analyzing it.

This made sense 15 years ago when SIEMs were on-premises appliances with fixed capacity. If you wanted to store more data, you needed more hardware. More disks, more processors, more indexing engines, all bundled together.

But that model is fundamentally misaligned with how security operations actually work. Not all data needs to be "hot" and immediately queryable. Some logs are for real-time alerting. You need instant access, high performance, complex correlation. Other logs are for historical analysis, compliance, and forensics. You need them to exist and be searchable, but not in milliseconds.

Charging the same premium price for both use cases forces impossible choices.

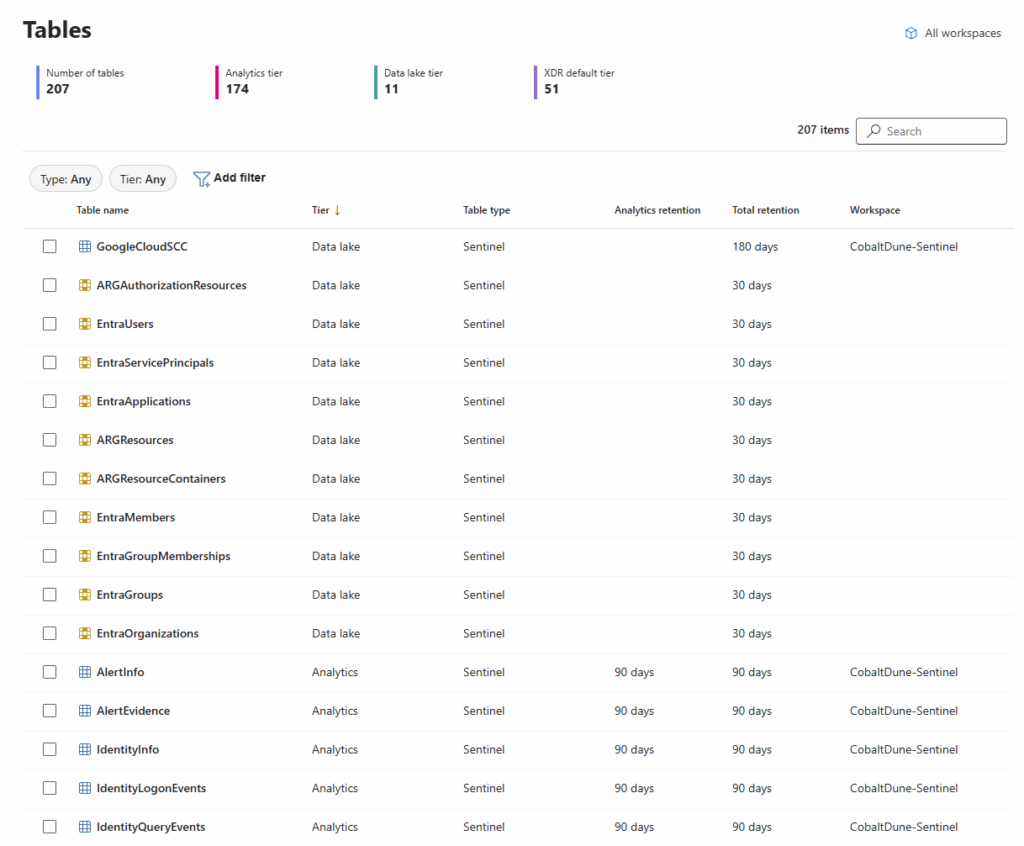

Microsoft's general availability release of the Sentinel data lake introduces a cost model worth understanding in detail, because it fundamentally alters the economics.

The headline: up to six times lower storage costs compared to traditional analytics-tier pricing.

How they achieve it: billing based on compressed data size, with a standardized 6:1 compression ratio applied uniformly. Ingest 600 GB of raw logs, get billed for 100 GB.

Why it matters: you can now afford to keep data you previously had to discard.

The architecture separates storage from compute. The data lake tier is optimized for long-term retention (up to 12 years) without the overhead of maintaining hot indexes. You're not paying for real-time query performance on data you only need to access occasionally. But when you do need it, it's there and it's queryable. Not instant, but accessible. Seconds to minutes instead of hours or "archived to tape, good luck."

This isn't just a discount. It's a different category of cost. The analytics tier (what you use for real-time detection, hunting, and dashboards) remains premium-priced because it needs premium performance. The data lake tier is for everything else.

When storage costs drop by 85%, the entire conversation about data collection changes.

Suddenly, NetFlow becomes affordable. You can justify keeping DNS logs for years. Those verbose application logs that developers insisted would help with security investigations but you couldn't justify ingesting? Now you can.

The strategic shift is from "what can we afford to collect?" to "what do we need to collect to actually find sophisticated threats?"

This opens detection strategies that simply weren't viable before:

Behavioral baselining at scale. You can't establish what's normal for a user, system, or application without months of historical data. With long-term, affordable storage, you can build those baselines and detect anomalies that are invisible in shorter time windows.

Historical threat hunting. When threat intelligence reveals a new IOC or TTP, you can retroactively hunt for it across years of data. How many times has your team learned about an attack technique and wondered, "Were we hit by this six months ago?" Now you can actually answer that question.

Low-and-slow attack detection. APT groups move carefully. They might compromise one system, wait weeks, move laterally to another, wait again. These patterns only emerge when you can correlate events across extended timeframes.

Compliance without compromise. Regulations that demand multi-year audit trails stop being a budget-busting burden. You can meet retention requirements and still have the data accessible for security purposes.

The new model introduces a new operational question: what goes where?

This isn't just a cost optimization exercise. It's about matching data characteristics to storage tiers.

Analytics tier (hot storage): Real-time detection rules, interactive hunting, dashboards, automated response. This is for data you need instantly and frequently. Security alerts, authentication events, EDR telemetry, high-confidence threat indicators.

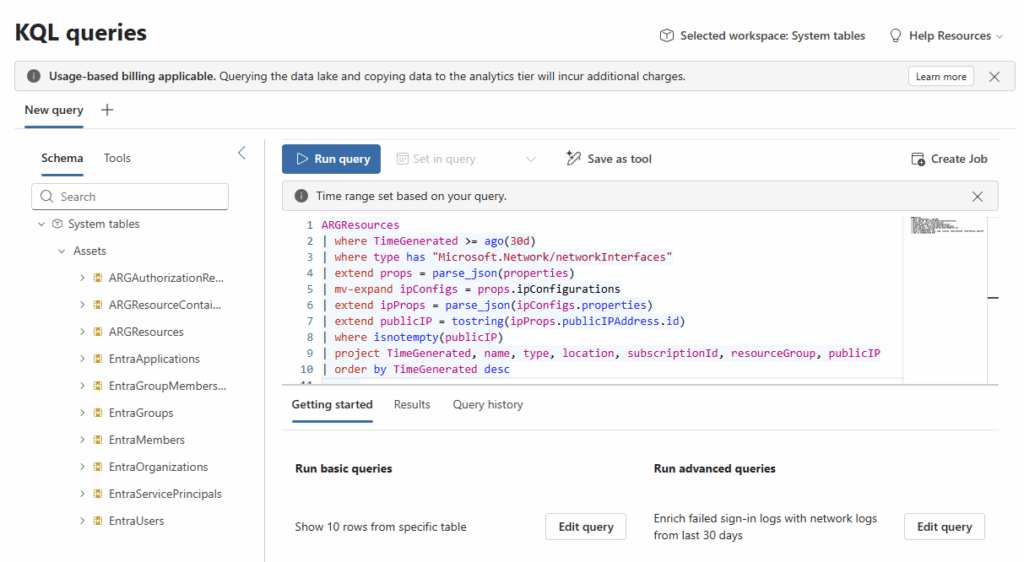

Data lake tier (cold storage): Historical analysis, forensics, compliance, large-scale analytics jobs. This is for data you need to exist and be searchable, but not in milliseconds. NetFlow, DNS, verbose application logs, cloud resource logs.

The strategic nuance: you can send data directly to the data lake tier, or you can send it to analytics first and let it automatically mirror to the lake. The former saves ingestion costs. The latter gives you real-time access during the retention window before it ages into cold storage.

Here's a practical example: Authentication logs from Entra ID. You want those in analytics tier for real-time alerting on suspicious logins. But you also want them in the data lake for historical investigations. Solution: ingest to analytics, it automatically copies to the lake, and you have both real-time detection and long-term forensic capability.

Contrast that with NetFlow data. You're probably not running real-time analytics rules on every network flow. You're using it for investigations and threat hunting. Send it straight to the data lake. Save the premium ingestion cost, but still have it available when you need to reconstruct network activity during an incident response.

Here's the catch: storage is cheap, but compute isn't free.

The data lake model decouples storage and compute, which creates a new cost variable. Queries are charged per gigabyte of data scanned. This is actually transparent and fair (you pay for what you use) but it requires discipline.

An analyst running an overly broad query against years of unfiltered data can rack up compute costs quickly. "Show me all authentication events for the last five years" might scan terabytes. That's expensive.

This introduces a new operational discipline: query optimization matters. You need SOC teams trained to write efficient KQL. You need governance around who can run interactive queries versus scheduled jobs. You need monitoring on compute spending the same way you monitor ingestion.

The good news: Sentinel's new cost management capabilities provide visibility. You can set thresholds, get alerts when usage spikes, and identify which queries or analysts are driving costs. This isn't a black box.

The realistic assessment: most organizations will still spend significantly less overall, even accounting for query costs, because the storage savings are so substantial. But it's a different operational model that requires new habits.

The next time someone asks, "How much will that log source cost us?" the answer is different.

For data going to the analytics tier, the math is familiar. But for the massive-volume, lower-urgency sources that you've been ignoring or sampling? The calculus has changed.

You can now afford to be greedy about data collection. That doesn't mean reckless. You still need strategy around what provides security value. But the economic constraint has loosened dramatically.

For security leaders building business cases, the pitch changes. Instead of justifying why you need to spend more on the SIEM, you're demonstrating how you can expand visibility, improve detection, and meet compliance requirements while reducing overall TCO.

The data lake model isn't perfect. It requires rethinking operational processes, training teams on new tools, and building governance around query costs. But it solves the core problem that's been constraining security operations for a decade: the impossibility of comprehensive visibility within realistic budgets.

When you can afford to see everything, you can start focusing on what actually matters. Finding the threats that are already inside your environment, waiting to be discovered in the data you finally decided to keep.